Background

Historical Occupation Profiles explain what ancestors actually did for a living and how those occupations shaped the records genealogists rely on today.

Occupation Overview

Blacksmiths were skilled tradesmen who shaped iron and steel into tools, hardware, horseshoes, wagon parts, agricultural equipment, and countless everyday necessities. Throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries, nearly every town and rural community depended on at least one blacksmith.

Unlike wage laborers in large industries, blacksmiths often operated independent shops, apprenticed under established masters, and developed long-standing relationships within their communities. Their occupation combined craftsmanship, physical labor, and business management.

How the Job Was Described

Historical records typically use:

- blacksmith

- smith

- village smith

- farrier (specializing in horseshoeing)

- wheelwright (wagon-building, related trade)

- ironworker

In some census entries, the simple term “smith” appears. In others, blacksmiths may be grouped under “mechanic,” especially in earlier records.

Apprentices may be listed separately, often as “apprentice blacksmith” or simply “apprentice.”

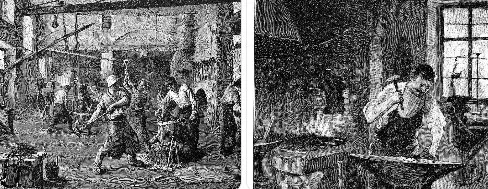

Duties & Daily Work

Blacksmiths heated iron in a forge and shaped it using hammers, anvils, and specialized tools. Their work commonly included:

- Shoeing horses

- Repairing wagons and farm equipment

- Forging hinges, nails, and hardware

- Creating tools such as plowshares and axes

- Performing custom metalwork

Because transportation and agriculture depended heavily on iron tools and horses, blacksmiths were central to both rural and urban economies.

In small communities, the blacksmith shop often functioned as both a workplace and a social gathering point.

Tools, Equipment & Work Environment

Blacksmith shops revolved around:

- Forge and bellows

- Anvil

- Hammers and tongs

- Swage blocks and chisels

- Quenching troughs

The environment was hot, smoky, and physically demanding. Sparks and heavy tools created ongoing risk of injury.

Shops were usually located in visible town centers or along main roads, increasing public visibility and documentation.

Apprenticeship & Business Structure

Blacksmithing was commonly learned through apprenticeship. Young men often began as apprentices in their teenage years and progressed to journeymen before establishing their own shops.

Records may appear in:

- Apprenticeship contracts

- Probate records (if a shop and tools were inherited)

- Business licenses

- Local directories

- Advertisements in newspapers

Blacksmiths frequently advertised services in local newspapers, especially in growing towns.

Records Created by Blacksmithing

Because many blacksmiths operated independent shops, records may surface in:

- City and rural directories

- Tax rolls

- Business licenses

- Probate inventories listing tools and shop equipment

- Court records involving debts or contracts

- Newspaper advertisements and notices

The visibility of a shop-based trade often makes blacksmiths easier to trace than transient laborers.

A Note on Historical Context

Before widespread mechanization and automobiles, communities relied heavily on horse-powered transportation. As a result, blacksmiths were essential to daily life.

With the rise of industrial manufacturing and later automotive repair shops, the traditional village blacksmith gradually declined. Understanding this transition helps explain why later generations may shift from “blacksmith” to “machinist,” “mechanic,” or factory work in census records.

Newspapers & Periodicals

Blacksmiths appear in newspapers through:

- Business advertisements

- Announcements of shop openings or relocations

- Notices of apprenticeship

- Estate sales involving shop equipment

- Community mentions tied to prominent local figures

In rural communities, the blacksmith was often well-known and socially visible.

Risks, Accidents & Legal Exposure

Although not as catastrophic as mining or rail work, blacksmithing carried risks:

- Burns from hot metal

- Eye injuries from sparks

- Crushing injuries from heavy tools

- Fire damage to shops

Serious incidents could result in court cases, coroner’s inquests, or newspaper reports.

Industry Terminology (Selected)

- Forge – Furnace used to heat metal

- Anvil – Heavy iron block for shaping metal

- Farrier – Specialist in horseshoeing

- Journeyman – Skilled worker who completed apprenticeship

- Bellows – Device used to intensify the forge fire

These terms frequently appear in probate inventories, advertisements, and trade notices.

Selected Free Research Starting Points

Researchers may find useful background materials and, in some cases, occupational documentation through:

- Library of Congress: historic photographs and trade documentation

- National Archives: apprenticeship, military blacksmith roles, and federal trade records

- State archives and historical societies with craft or trade collections

- Nonprofit and scholarly sites focused on traditional trades

- Internet Archive and HathiTrust: blacksmith manuals, trade publications, and instructional books

These sources often provide valuable context for understanding tools, training, and business practices.

Why Blacksmiths Matter to Genealogical Research

Blacksmiths were skilled tradesmen whose work tied them closely to their communities. Understanding the structure of apprenticeship, shop ownership, and tool inheritance helps genealogists interpret occupational continuity, social standing, and business records across generations.

If you’d like this information in a clean, printable, and well-organized reference format, this topic is also included in the Quicksheet Vault. The Vault is designed for researchers who prefer working tools they can save, print, and reuse—whether that means building a personal binder of key resources or keeping reliable references close at hand. You can learn more about the Quicksheet Vault HERE